In two judgments rendered on February 22, the Strasbourg judges decided that the human rights of 14 Jehovah’s Witnesses had been violated.

On February 22, 2022, Russia was hit by two judgments of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). The two judgments addressed six different cases concerning the mistreatment of 14 local Jehovah’s Witnesses. Russia adopts a faulty notion of “extremism,” which allows for banning religious organizations as “extremist” even when they do not practice nor advocate violence, simply based on the fact that they present their faith as “superior” to others, including the faith of the Russian Orthodox Church. Obviously, all religions believe that they offer a better path than others, including the Russian Orthodox Church itself. Nonetheless, the Jehovah’s Witnesses were considered “extremist,” and “liquidated” in Russia by the Supreme Court on April 20, 2017.

Both before and after the 2017 Supreme Court decision, individual Jehovah’s Witnesses and their local congregations were detained or subject to searches by the notorious Federal Security Service (FSB) and other police agencies, which tried to harass them in their normal religious activities and to seize “extremist” literature and other materials.

In the case of Cheprunovy and Others v. Russia, the applicants were individual Jehovah’s Witnesses and the local organization of the Jehovah’s Witnesses in Kostomuksha, a town located in the Republic of Karelia, Russia, near the border with Finland. Both the individual believers’ flats and the local organization were raided by the FSB between 2010 and 2012. “Bibles, magazines and books, and other personal items, such as computers, video-recordings, writing pads and notebooks” were seized.

In the case of Zharinova v. Russia, a Jehovah’s Witness woman from Ivanteyevka, in the Moscow Oblast, called Yekaterina Nikolayevna Zharinova was stopped and taken to the local police station on March 17, 2011, while she was engaged in door to door preaching. She was released after some hours, but personal belongings and religious literature were seized. No record of her detention was drawn up.

Loading...

Loading...

It is important to note that the theme the European judges had to decide was not whether the Jehovah’s Witnesses are “extremist,” and Russia was entitled to ban them, which is the subject matter of different ECHR cases. In both Cheprunovy and Others and Zharinova, the question was whether the human rights and religious liberty of those involved had been violated by the searches, seizures, and detention.

Loading...

Loading...

The Zharinova case involved the additional aspect that her detention had not been registered, which amounted to unauthorized deprivation of liberty under Article 5.1 of the European Convention on Human Rights. In both cases, Russia’s defense was that law enforcement personnel is authorized by the law to search for “extremist” material. In Cheprunovy and Others the searches had been either authorized through a warrant or validated post factum by courts of law. In Zharinova, the behavior of the officers was justified, according to Russia, by the fact that they were aware that courts of law had declared the Jehovah’s Witnesses and their literature “extremist,” and had reasons to believe that preaching their faith was not authorized.

The ECHR did not accept these arguments. It reiterated the important principle that when religious liberty and other human rights are at stake, relying on existing laws, administrative regulations, and court decisions (not to mention the police officers’ interpretation of decisions) is not enough. Even when searches and detention appear “lawful in domestic terms (…) it remains to be ascertained whether the impugned measures were ‘necessary in a democratic society’” and “proportionate.”

The ECHR concluded in Cheprunovy and Others that “the searches were carried out without relevant and sufficient grounds and in the absence of safeguard that would confine their impact to reasonable bounds” and were thus not “necessary in a democratic society.” In Zharinova, the judges also regarded as disproportionate the fact that a woman who had exhibited her ID documents and was not resisting the officers was brought to a police station and detained for several hours.

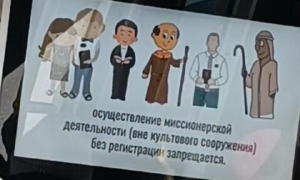

Importantly, the ECHR also stated that “the disruption of the applicant’s [Zharinova] door-to-door preaching, followed by her detention and seizure of religious literature amounted to an ‘interference by a public authority’ with her right to manifest her religion,” which is forbidden by Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Once again, the ECHR has affirmed that door-to-door preaching is a religious activity the authorities cannot forbid, which will probably have an impact on other pending cases where the Jehovah’s Witnesses confront Russia on the same subject.

The ECHR clearly understood that in both cases Russian citizens were subject to measures only because they were “active members of the local congregations of Jehovah’s Witnesses,” as the Cheprunovy and Others judges said. This is a clear violation of article 9, which prohibits religious discrimination and guarantees religious liberty.

Both decisions are final, and Russia should pay a total of over 99,000 euros ($112,323 U.S.) in compensation for the violations.