Courts have twice fined Zhangazy Biimbetov, a Jehovah’s Witness from Oskemen, 2 months’ average wages for sharing his faith. In July he challenged the constitutionality of the ban on and punishments for sharing faith. The Constitutional Court accepted the case on 4 October but has not yet set a date for a hearing, which will be held in public. No one was available at the regime’s Religious Affairs Committee to explain why individuals continue to be punished for talking to others about their faith.

The 2011 Religion Law bans any sharing of faith by anyone except individuals who have gained state registration as “missionaries”. To gain such status, an individual needs to provide a range of documents, including a certificate from a registered religious organisation appointing them as a “missionary”. The regime keeps such individuals under tight scrutiny (see below).

Biimbetov argues in his Constitutional Court suit that bans in the Religion Law on sharing faith and punishments in the Administrative Code violate provisions of the Constitution guaranteeing freedom of speech and conscience, and equality for all under the law. He also argues that they violate provisions of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights guaranteeing freedom of religion or belief and expression (see below).

Under the Constitutional Court’s procedures, hearings are public, interested parties can present their views and the Court’s final decision is made public (see below).

No one was available at the regime’s Religious Affairs Committee in the capital Astana to explain to Forum 18 why individuals continue to be punished for talking to others about their faith. Its chair, Yerzhan Nukezhanov, did not answer his phone on 6 and 7 November. Nor too did Deputy Chairs Bauyrzhan Bakirov and Anuar Khatiyev (see below).

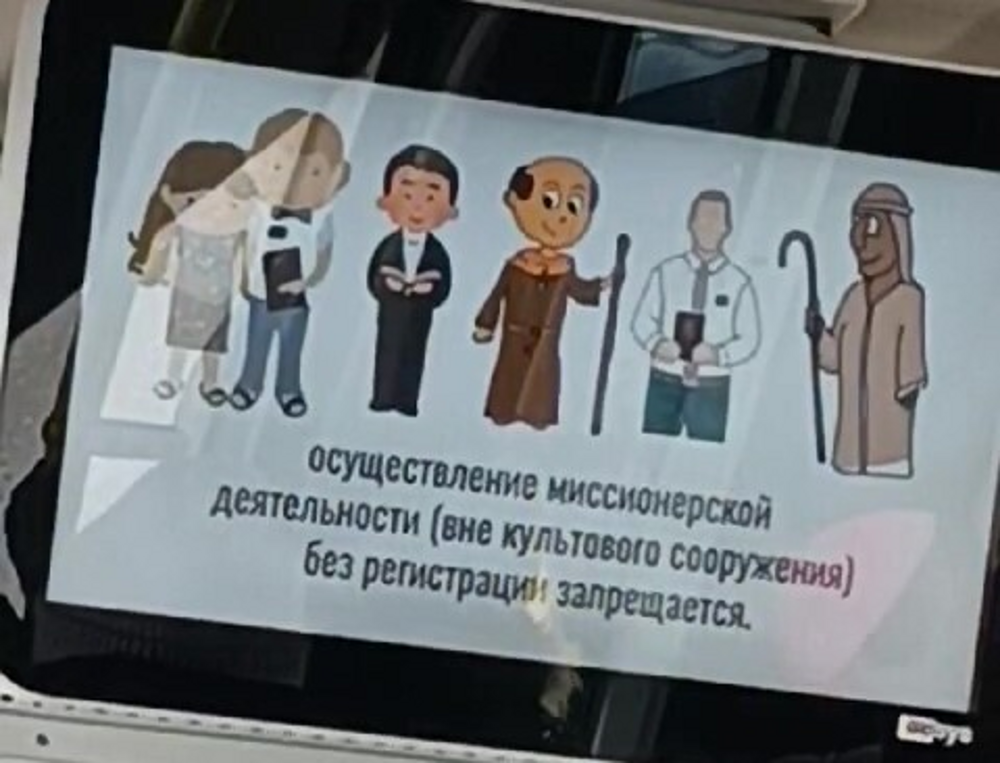

Regime-sponsored warnings against sharing faith are widespread in advertisements – including on bills for utilities and on public transport. In summer 2024, utility bills included a warning: “BE VIGILANT if unknown people on the street or in public places forcibly conduct conversations on God and existence.” The warning instructs those who see people discussing religion or offering religious literature in public places to call the police (see below).

In one District of southern Kazakhstan, Shu District close to the border with Kyrgyzstan, police in March and April raided four worship meetings of three local Protestant churches. Officers filmed those present, demanded that some write statements explaining why they were present and issued six summary fines. Two of the church leaders were also fined in court under Administrative Code Article 490, Part 3 (“Carrying out missionary activity without state registration (or re-registration)”) (see below).

Since at least 2019, Police have on occasion used Administrative Code Article 449, Part 1 (“Harassment in public places”) rather than Administrative Code Article 490 to try to punish those sharing their faith, particularly Jehovah’s Witnesses. Such use of Article 449 appears to be increasing. However, judges dismissed all 10 known cases that reached court in 2024 (see below).

Administrative Code Article 449 “has nothing to do with adherents of any religious denomination”, Andrei Grishin of the Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and the Rule of Law notes. “According to this logic, anyone can be held accountable for asking any passer-by the question: ‘Can you tell me what the time is?'” (see below).

Police and religious affairs officials continue to bring to court cases to punish individuals for posting religious materials online without state permission, as well as for trying to import religious literature without state permission (see forthcoming F18News article).

Tight regime control of “missionaries”

The 2011 Religion Law bans any sharing of faith by anyone except individuals who have gained state registration as “missionaries”. To gain such status, an individual needs to provide a range of documents, including a certificate from a registered religious organisation appointing them as a “missionary”. They can only use state-approved material and can only operate in state-approved places. Registration must be renewed every year.

Aigul Karibayeva, Chief Specialist of Zhambyl Regional Religious Affairs Department, noted in an article on the local Znamya Truda news website on 12 August that the Department had registered 8 people “with the right to conduct missionary activity in [registered] religious organisations of the Region”.

“The Religious Affairs Department regularly studies their sermons and events,” Karibayeva added. “The results of the investigation found the absence of violations of the law threatening the stability of the state and inciting inter-confessional and inter-ethnic intolerance.”

No one was available at the regime’s Religious Affairs Committee in the capital Astana to explain to Forum 18 why individuals continue to be punished for talking to others about their faith. Its chair, Yerzhan Nukezhanov, did not answer his phone on 6 and 7 November. Nor too did Deputy Chairs Bauyrzhan Bakirov and Anuar Khatiyev.

A colleague of Beimbet Manetov, head of the Religious Affairs Committee’s Department of Law Enforcement Practice in the Field of Religious Activities, told Forum 18 on 6 November that he was in a meeting. He did not answer his phone on subsequent calls. He had insisted to Forum 18 in February 2022 that individuals had to be fined if they break the law. Asked why courts punish individuals for exercising freedom of religion or belief, he responded: “I can’t comment on court decisions.”

Regime warnings against “missionary activity”

Regime-sponsored warnings against sharing faith are widespread in advertisements – including on bills for utilities and on public transport.

In summer 2024, utility bills included a warning: “BE VIGILANT if unknown people on the street or in public places forcibly conduct conversations on God and existence, offer you to buy some religious literature for a symbolic price or receive as a gift, or ask strange questions: ‘Does your life satisfy you?’, ‘The world is unsettled at the moment, do you want to know why?’ etc.”

The warning adds: “It is possible that you are facing a recruiter and HIS GOAL IS TO DRAG YOU INTO THE RANKS OF ADEPTS OF A DESTRUCTIVE RELIGIOUS MOVEMENT.” The warning instructs those who see people discussing religion or offering religious literature in public places to call the police.

Warnings are also posted on social media. Many of these posts come from organisations that receive government grants.

Sarkan District Youth Centre in Almaty Region warned readers in an Instagram post on 7 June not to attend unregistered religious events as these are illegal. It noted that organisers face punishment under Administrative Code Article 453 (“Production, storage, import, transfer and distribution of literature containing .. social, national, clan, racial, or religious discord”) and Administrative Code Article 490.

The post went on to warn: “If you see on the street or in a residential area people distributing books, booklets, brochures or religious leaflets, then you should know that this is illegal distribution of religious literature!”

In a short Instagram video on 25 September, the Centre for the Study of Religion in Astana warned that those who share their faith are subject to a fine of 100 Monthly Financial Indicators (MFIs) (2 months’ average wages) under Administrative Code Article 490. The Centre receives large state grants, including 405 million Tenge in 2023.

The government-backed Religion in Atbasar District, based in Akmola Region, published the same 8-second video on its Instagram page on 27 September.

Twice fined for sharing faith

Zhangazy Biimbetov, a 65-year-old Jehovah’s Witness from the eastern city of Oskemen, has twice been fined for sharing his faith.

In March 2013, police in Oskemen detained Biimbetov in his home, took him to the police station, photographed and fingerprinted him. In April, the Regional Religious Affairs Department summoned him. Officials prepared an administrative case against him for “illegal missionary activity” and sent it to court. In May, Oskemen’s Specialised Administrative Court found him guilty and fined him 100 MFIs (2 months’ average wages). He failed to overturn the fine on appeal.

Ten years later, officials brought a new case against Biimbetov to punish him for sharing faith with a home owner in Oskemen without state permission on 4 March 2023. She complained to the police more than 7 weeks later. Police and a regional religious affairs official brought an administrative case against him.

On 12 July 2023, Oskemen Specialised Administrative Court found Biimbetov guilty under Administrative Code Article 490, Part 3. Judge Alma Kuzbosynova fined him 70 MFIs (6 weeks’ average wages), according to the decision seen by Forum 18.

East Kazakhstan Regional Court rejected his appeal on 17 August. “From Biimbetov’s appeal, it is clear that he spends part of his time each month sharing the biblical news of the Creator with other people,” the court decision (seen by Forum 18) notes. “He conducts this religious activity by means of personal conversations with people who want it, and by providing practical advice from Holy Scripture.”

In September 2023, Biimbetov took his case to the Supreme Court in Astana, according to court records. On 27 October 2023, the Court refused to consider the case.

Constitutional Court challenge to sharing faith restrictions

Zhangazy Biimbetov lodged a suit to the Constitutional Court in Astana in July, challenging the constitutionality of restrictions on sharing faith.

In particular, Biimbetov is challenging:

– Article 1, Part 5 of the Religion Law which defines missionary activity as “the activity of citizens of the Republic of Kazakhstan, foreigners and stateless persons, aimed at disseminating religious teaching on the territory of the Republic of Kazakhstan for the purpose of converting to a religion”.

– Article 8, Part 1 of the Religion Law which declares: “Citizens of the Republic of Kazakhstan, foreigners and stateless persons carry out missionary activity after undergoing registration.”

– Administrative Code Article 490, Part 3 which punishes “Carrying out missionary activity without state registration (or re-registration)” with a fine of 100 MFIs (2 months’ average wages), plus – if the individual is a foreign citizen – deportation.

Biimbetov argues that these legal provisions violate rights under:

– the Constitution’s Article 20 (which guarantees freedom of speech) and Article 22 (which guarantees freedom of conscience), making the possibility of their implementation dependent on the permission of the state. As a result, the basic inalienable rights have turned into special alienable rights granted at the discretion of a state body, which contradicts Article 12, Paragraphs 1 and 2 (which guarantee human rights for all) of the Constitution;

– the Constitution’s Article 39, Paragraph 1 (which narrowly defines how an individual’s rights can be restricted), as the contested provisions/restrictions do not pursue any of the socially significant goals for which such a restriction is permitted and listed;

– the Constitution’s Article 14, Paragraph 1 (which guarantees equality before the law), as the contested provisions establish a requirement to obtain registration in order to share opinions on religious issues, while the law does not contain such requirements for disseminating opinions on other issues. These differences have no objective and reasonable justification, and therefore the contested provisions contradict the principle of equality before the law and the court;

– Article 14 (equality before the courts), Article 18 (freedom of thought, conscience and religion) and Article 19 (freedom of expression) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ratified by Kazakhstan in 2005), which have priority over national legislation, and also the case law of the United Nations Human Rights Committee, whose jurisdiction Kazakhstan recognises.

Under the Constitutional Court’s procedures, hearings are public. All interested parties can present their views (such as the applicant, ministries, prosecutor’s office officials, or the Ombudsperson). Other people and organisations can submit their views (though doing so in person requires special approval). The Court’s final decision is made public.

The Constitutional Court accepted Biimbetov’s case on 4 October 2024, according to its website. The Court assigned Judge Sergei Udarstev as the rapporteur. The Court website gives no date yet for a hearing.

1 District, 8 fines

Two of the church leaders were also fined in court under Administrative Code Article 490, Part 3 (“Carrying out missionary activity without state registration (or re-registration)”).

On 27 March, Shu District Court fined Pastor Valter Mirau 100 MFIs (2 months’ average wages). On 30 April, Zhambyl Regional Court rejected Pastor Mirau’s appeal, according to the decision seen by Forum 18.

On 23 May, Shu District Court fined 76-year-old Pastor Andrei Boiprav 100 MFIs (2 months’ average wages). On 20 June, Zhambyl Regional Court rejected his appeal, according to the decision seen by Forum 18.

Saule Baibatshayeva, the official overseeing non-Muslim communities at the Religious Affairs Department of Zhambyl Regional Akimat [administration], told Forum 18 in May that she knew about the raids and fines on Protestants in Shu District in March and April. “The police are to blame,” she insisted. “They take their own measures under the Administrative Code. There was no order from us.” She claimed that she and her colleagues try to stop police from punishing unregistered Christian communities for meeting for worship.

Some “missionary activity” prosecutions fail

Police and prosecutors do not always succeed when trying to punish individuals for speaking about their faith to others.

On 11 November 2023, a resident in the southern city of Turkistan called the police claiming to be anxious after Jehovah’s Witness Gulzhavkhar Kholboyeva came to her door and offered her a card with links to the Jehovah’s Witness website. Court decisions note that when the resident asked her to leave, Kholboyeva “apologised and left immediately”.

A police officer drew up records of an offence against Kholboyeva, first under Administrative Code Article 449, Part 1 (“Harassment in public places”) and then also under Administrative Code Article 490, Part 3 (“Carrying out missionary activity without state registration (or re-registration), as well as the use by missionaries of religious literature, information materials with religious content or religious items without a positive assessment from a religious studies expert analysis, and spreading the teachings of a religious group which is not registered in Kazakhstan”).

Turkistan Specialised Administrative Court dismissed the case against Kholboyeva under Administrative Code Article 449 on 9 January 2024. The court dismissed the case under Article 490 on 22 January, according to the court decisions seen by Forum 18.

On 19 March, residents in Aktau called the police about Jehovah’s Witness Anton Kotovich, who was sharing his faith from door to door with another man. The following day, a police officer drew up a record of an offence against him under Administrative Code Article 490, Part 3. Police also seized Kotovich’s passport.

On 22 May, Aktau Specialised Administrative Court dismissed the case against Kotovich as police had not adequately documented materials seized from him, according to the decision seen by Forum 18. The court also ordered the return of his passport.

A Pentecostal, Sergei Orlov, spoke in a flat in Almaty on Sunday 10 March to a group of church members who were meeting to mark the 8 May international women’s day. He spoke of women in the Bible. He knew all of those present, except one man who filmed the meeting, he told Forum 18.

On 13 March, the man reported the meeting to the police, asking for the church to be investigated. The police passed the information to the city’s Religious Affairs Department.

On 1 April, the Religious Affairs Department summoned Orlov. Almaz Zhanamanov drew up a record of an offence against him under Administrative Code Article 490, Part 3 (“Carrying out missionary activity without state registration (or re-registration), as well as the use by missionaries of religious literature, information materials with religious content or religious items without a positive assessment from a religious studies expert analysis, and spreading the teachings of a religious group which is not registered in Kazakhstan”).

Orlov insisted there was no reason for officials to bring a case against him.

Asked why he had drawn up the record of an offence, Zhanamanov refused to explain. “On all questions you should apply officially to the Department,” he told Forum 18 in April.

Orlov tried to challenge the record of an offence. However, on 19 April, Almaty Inter-District Specialised Administrative Court rejected his suit, according to the decision seen by Forum 18.

On 2 May, Judge Dinara Kuzetayeva at the same court began hearing the case against Orlov under Administrative Code Article 490, Part 3. At a further hearing on 24 May, she dismissed the case “for absence of an offence”, according to the decision seen by Forum 18. It notes that the man who had attended the church meeting did not understand Russian and could not therefore explain what Orlov had said.

10 known “harassment” cases in 2024, all dismissed

Since at least 2019, Police have sometimes used Administrative Code Article 449, Part 1 rather than Administrative Code Article 490 to try to punish those sharing their faith, particularly Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Administrative Code Article 449 punishes: “Harassment in public places”. The punishment is a warning or a fine of 5 MFIs (3 days’ average wages).

Article 449 defines harassment as “an intrusive approach in public places for the purpose of buying, selling, exchanging or acquiring things in another way, committed by a person who is not a business entity, as well as for the purpose of fortune telling, begging, providing sexual services or imposing other services”.

Andrei Grishin of the Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and the Rule of Law notes the increased use of Article 449.

“True, when it is really necessary alternative accusations can be found, even if they are absurd,” Grishin wrote on 2 October 2024. “So far, such a saving straw has become Administrative Code Article 449, which in fact has nothing to do with adherents of any religious denomination.”

Grishin points out that individuals sharing their faith “do not impose any services on anyone. Everyone has the right to decide for themselves: believe it or not. According to this logic, anyone can be held accountable for asking any passer-by the question: ‘Can you tell me what the time is?’.”

At least 10 Jehovah’s Witnesses (in addition to Gulzhavkhar Kholboyeva – see above) have faced court cases for sharing their faith so far in 2024 under Administrative Code Article 449, Part 1.

The 10 were: Dilyara Stovba, Oksana Toropchina, Kuanysh Nurimbetov, Bolat Dilmanov, Yekaterina Grebennikova, Yelena Voronaya, Almas Doshkhozhayev, Lyubov Gracheva, Bibizat Sadvokasova, and Mukhambetjan Omarbekov. In all 10 cases, courts acquitted the individuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses told Forum 18. (END)